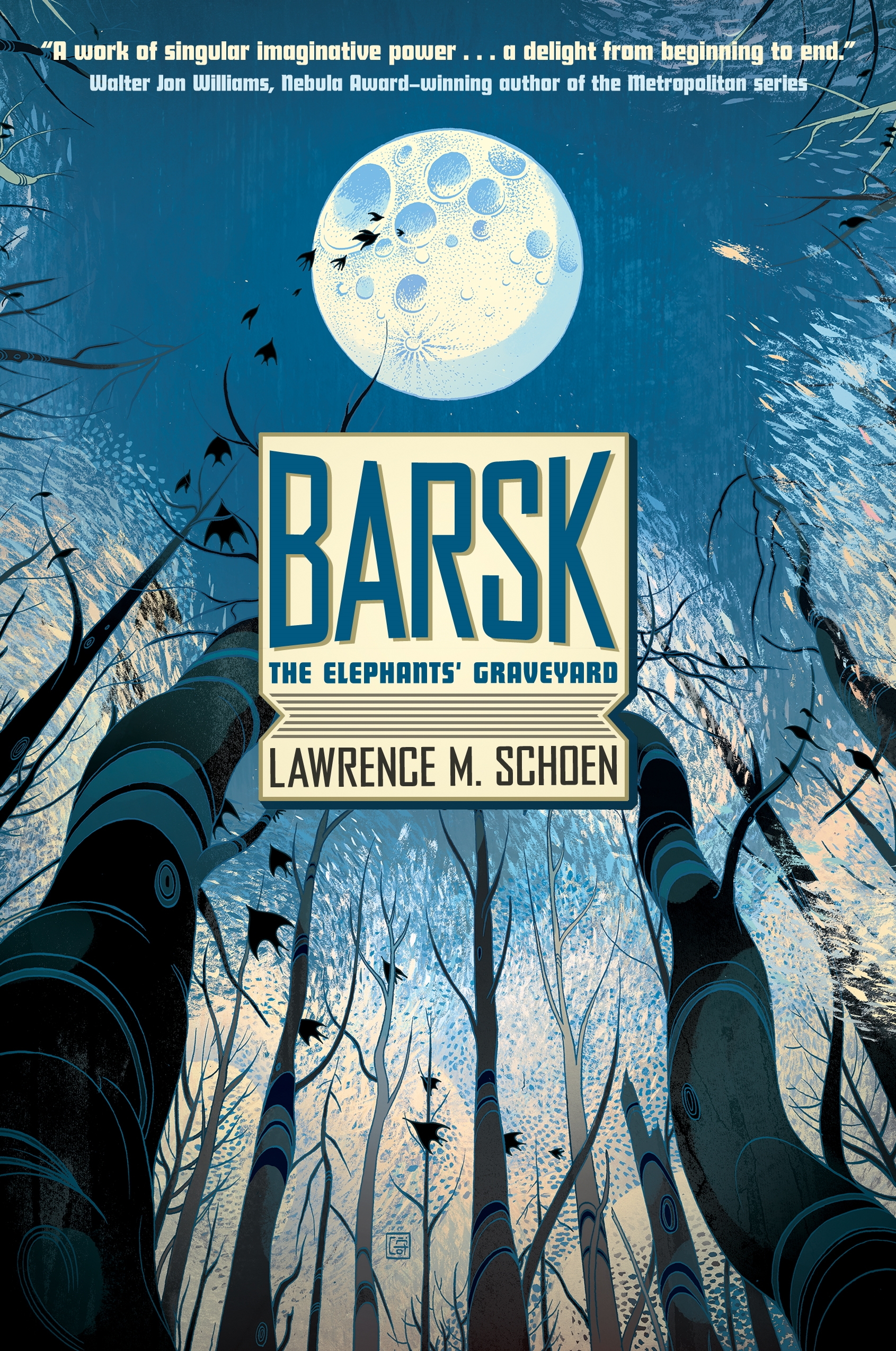

Just in time for the release of his new book, Barsk: The Elephants’ Graveyard, Lawrence M. Schoen stopped by for this interview. About Barsk:

The Sixth Sense meets Planet of the Apes in a moving science fiction novel set so far in the future, humanity is gone and forgotten in Lawrence M. Schoen’s Barsk: The Elephants’ Graveyard.

An historian who speaks with the dead is ensnared by the past. A child who feels no pain and who should not exist sees the future. Between them are truths that will shake worlds.

Me: Can you describe your writing for someone who is unfamiliar with it?

Lawrence: A lot of my past writing takes the form of light and humorous stories, enjoyable and entertaining reads. This is particularly true of the series of short stories, novellas, and novels that make up my Amazing Conroy series. With Barsk I went darker. Which is not to say that there are not amusing and light-hearted bits, but overall the tone is much more serious, as one would expect when dealing with themes like intolerance and death.

Would you want to live in the world of your book?

That’s a tough call. If I lived on any of the island rainforests of Barsk, that would mean I’m an anthropomorphic elephant (a Fant). While it might be very cool to make my home in a living city high in the trees, it would probably take a while to get used to having a trunk. Also, the Fant tend to eschew most technology and I can’t see myself going back to writing everything longhand.

Elsewhere though, on most of the hundreds of other worlds in the Alliance that I invented for the book, such a parochial view on hardware is rarer and I could have all sorts of cool gadgets (I’m not giving up my smart gear, sorry). But I still couldn’t be a human being, as there aren’t any. I’d have to get comfortable being some other race of Raised Mammal. And furry.

Why did you write this story?

When I was in junior high and high school, I had the misfortune to have social studies teachers who managed to convince me that history was nothing more than a boring list of names and dates. This was a huge disservice. I now realize that history is perhaps best conceptualized as a type of storytelling, and it can be as riveting and nuanced as the best work of fiction. But the damage was done, and even now, so many decades later, I still feel cheated. In many ways, Barsk began as an attempt to absolve that sin and talk about history from the perspective of someone who was making the study of it his life’s work. To show that despite it being old and dead it was also vibrant and alive. That led curiously to the not so metaphorical plotline of having a protagonist who could actually talk to the dead, as well as the further complication of what happens when the historian finds himself at the very heart of the events he’s supposedly chronicling.

What is compelling for you?

People. When I was growing up, I worked with my father at the swapmeet. We sold everything from lingerie to melon-ballers to cans of “liquid bandage,” and I did this every weekend from age five to eighteen, escaping only by going off to college. During those thirteen years I interacted with every flavor of humanity, every race, gender, socio-economic and educational level. I got to see what they had in common and how they differed, both as groups and individuals. That experience contributed to my pursuing a doctorate in psychology, and it’s what made me realize that each of us has a story to tell, if only someone would listen.

What surprised you while writing it?

The way things came together at the end.

I knew how everything ended (indeed, almost every word of Barsk’s epilogue was written more than twenty years ago). But the way all the character arcs and the various plotlines flowed together in such a satisfying result, I wasn’t expecting that. Clearly, my unconscious mind had it all planned out, but when it finally trickled into my awareness I was really amazed and pleased.

How will reading it make people feel?

I hope it will move people, and leave them emotionally impacted long after they turn the last page. I grew up reading Burroughs and Heinlein and Zelazny, and time and again I was on the receiving end of that “sense o’ wonder” that continues to fade in and out of fashion in our field. I strive to create that in my work (whether it’s currently fashionable to do so, or not, I can’t say). I want readers to relate to my characters, to care about their choices and lives. They’re very real for me, and I’d like them to come alive for my readers as well. At the end of Barsk, I want people to be asking what happens next to Jorl and Pizlo, as they would about real people who have crossed in and out of their lives.

Was there anything you did deliberately while crafting this novel (pacing, language, symbolism…)?

Oh yeah, all of that. Readers have consistently told me that my strengths are dialogue and characterization, and by extension my weaknesses are plot and pacing. So a lot of writing Barsk was about my striving to improve the way I create and manage both plot and pacing. I think all writers want to get better, to stretch and grow. The solution for me was to invest in a large number of subplots, and use my strengths to develop and explore them. Which is why all the POV characters have their own backstories and motivations for what they’re doing, and that informs the main storyline. Even some of the minor supporting characters have their own tiny narratives, because in their own minds they’re the heroes of their own stories.

Language is easier for me because, 1) it’s language, which is what I live for, 2) it emerges from the individual characters as manifested in their conversation and, hello, characterization and dialogue!

As for symbolism, I’m finding that people who read Barsk are adamant that I put in this or that object lesson, that the entire book is an allegorical statement about one thing or another, that it’s my personal soapbox. I honestly don’t believe this is the case. Are there symbols in the book? Sure, of course there are, and since I wrote it I must be the one to have put them in. But if I did, I don’t think it was in any kind of knowing, conscious, or deliberate way. But too, I don’t expect anyone to believe me however true that statement may be.

Why?

That really cuts to the question of “why do we write books in the first place?” I’m not one of those authors who raise the back of a hand to the forehead and with anguish in my voice proclaims that I simply have to write, that the words must come forth. I see other writers do that and it makes me roll my eyes. I don’t believe it, though I do believe that they may believe it. But you know what they say about that river in Egypt. But hey, if helps them to put words on the page, who am I to judge?

Part of why I write is to entertain, to tell a story. Part is to grow as person. Writing a novel is an odd exercise in personal exploration. If you do it right by the time you’re done you know new things about yourself that you hadn’t realized were true, or that you had in you. It can be a mild learning experience or a hugely transformative crucible, and you’re probably not going to know which until you’re on the other side of the book.

And that’s a good thing, I think. Because writing a novel should be an intensely personal experience, for both the author and the audience. Writing Barsk changed the way I see the world, and if I did it right it should have a similar effect on the reader. We’ll see.

Lawrence M. Schoen holds a Ph.D. in cognitive psychology, has been nominated for the Campbell, Hugo, and Nebula awards, is a world authority on the Klingon language, operates the small press Paper Golem, and is a practicing hypnotherapist specializing in authors’ issues.

His previous science fiction includes many light and humorous adventures of a space-faring stage hypnotist and his alien animal companion. His most recent book, Barsk, takes a very different tone, exploring issues of prophecy, intolerance, friendship, conspiracy, and loyalty, and redefines the continua between life and death. He lives near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with his wife and their dog.

Website: http://www.lawrencemschoen.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lawrencemschoen

Twitter: @klingonguy

Leave a Reply